Collection

The Origins

At the time of its creation, the collection of the Fondation William Cuendet & Atelier Saint-Prex was formed partly by the engravings and etchings by Dürer and Rembrandt assembled by the pastor William Cuendet (1886-1958), and partly by those donated by Pietro Sarto (born in 1930), custodian of the archives of the Villette and Saint-Prex workshops, comprising prints by the many contemporary artists who had worked there. Over the years, this original core was supplemented by gifts from the collection of painter-engraver Gérard de Palézieux. The Fondation has recently been strengthened by yet more donations, bequests and acquisitions.

-

-

Atelier de Saint-Prex and Pietro Sarto

-

Gérard de Palézieux's legacy

The William Cuendet collection

In the mid-1970s, with the help of Gérard de Palézieux, the heirs of William Cuendet (1886-1958) established contacts with members of the Atelier de Saint-Prex, notably Albert-Edgar Yersin and Pietro Sarto. Their shared passion for the art of printmaking prompted them to bring together under the same roof the treasures collected by the pastor since his youth - more than two hundred prints by Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt van Rijn - and the productions of artists working daily in the workshop. As a pastor, William Cuendet had been keenly sensitive to Dürer's wood and copper engravings of Scriptural stories in his suites of Passions, as he was to Rembrandt’s etchings, a century later, depicting episodes from the life of Christ. Prescient thinking led Cuendet and those close to him to form a Foundation which would steward this new collection.

William Cuendet (1886-1958)

Born in 1886 in Tizi-Ouzou, Algeria, where his father worked as a missionary for fifty years and translated the Bible into Kabyle, William Cuendet spent much of his childhood in the village of Djemâa Saridj, in the heart of the mountains, then in Algiers, where as a schoolboy he is said to have started collecting his first reproductions of engravings. He then moved to Switzerland to complete his studies at the Faculté libre de Théologie in Lausanne. He went on to study at the Sorbonne, Yverdon and Glasgow, and the subject of his much-praised thesis was the religious philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. From 1911 to 1924, he was first a substitute, then pastor, at the French Church in Zurich. Back in Lausanne, he was appointed pastor of the Marterey parish in 1924, a post he held until 1949. In 1914 he married Andrée Mercier-de Molin, the daughter of Lausanne architect and art patron Jean-Jacques Mercier, with whom he had four children: a son, Olivier, and three daughters, Madeleine, Mireille and Danielle.

In addition to his ministry, William Cuendet played an important role in the social and theological life of his canton; he was the founder of the Friends of Protestant Thought and president of the Vaud Theological Society. A generous man who took an active interest in refugees during World War I, he had an ardent spirit, constantly striving for greater knowledge and understanding. His preaching was renowned not only for its intellectual mastery, but also its vigorous eloquence.

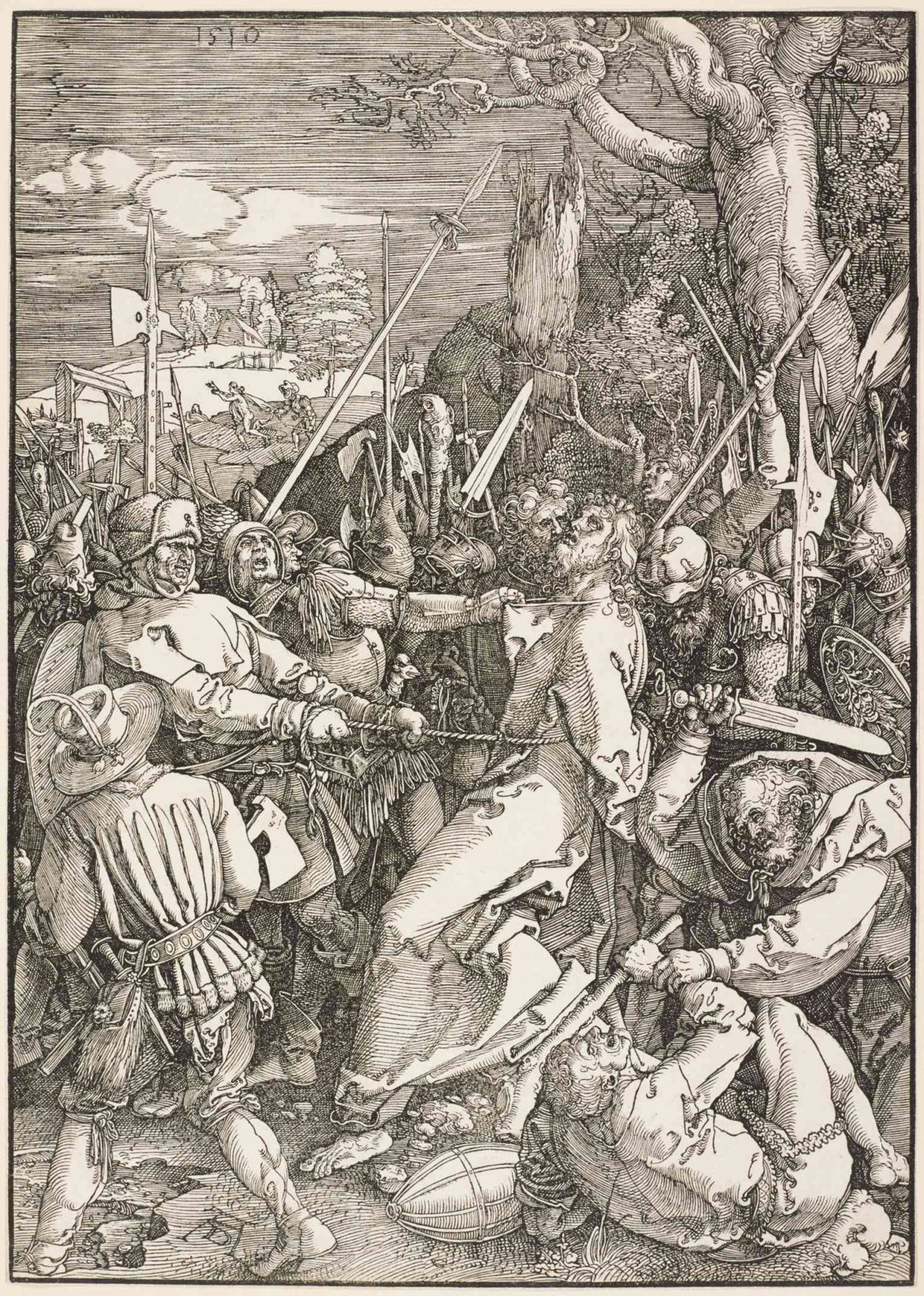

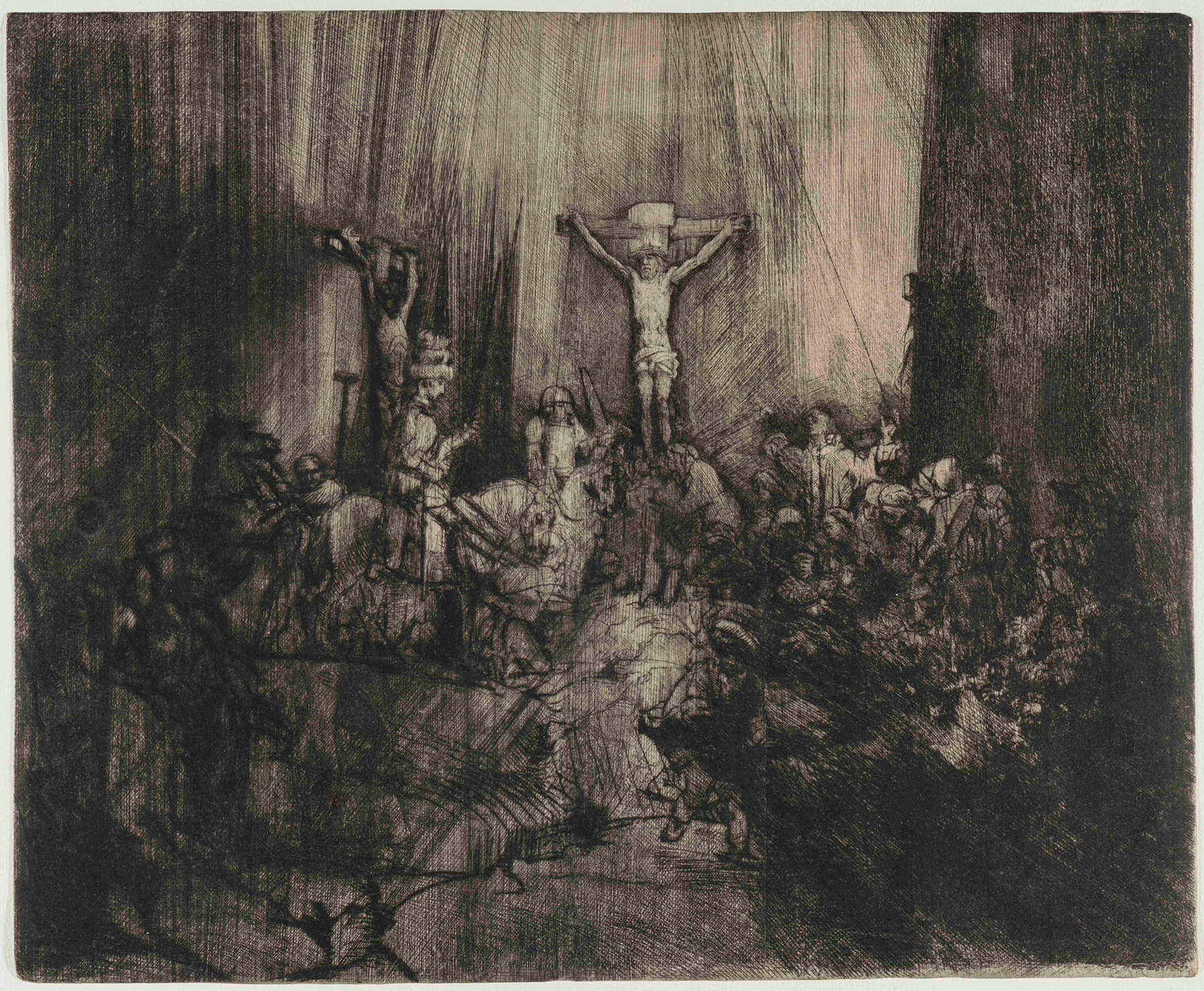

Driven by his ardent faith, William Cuendet was shaped by the lessons of the Gospels, and his precocious and demanding eye naturally gravitated towards images imbued with religious significance. Reflecting his concerns as a Christian, the prints he collected fed his reading of the Bible, building bridges between faith and art. According to his son Olivier, his collection of prints was built in a time when "claudelisation" was the regnant fashion. As Cuendet, an enthusiastic Christian, saw it, Albrecht Dürer, though he never adopted Luther's incendiary theses for himself, appeared to be an early Protestant—a man concerned by the Roman Church’s corruption, who advocated a return to Solus Christus and Sola scriptura. It was undoubtedly the religious content of their prints, which were faithful to the New Testament and particularly to the incarnation of the Son of God on earth, that led Cuendet to concentrate his collecting on Dürer and Rembrandt. In addition to their obvious talent, these two artists, separated by a century and a half, were united by their powerful, dramatic vision of Christ’s Passion. Each examined the story of Jesus, who died for the salvation of mankind, with a kind of fascinated compassion and a faith in His truth.

More than one hundred of Dürer's plates are devoted, in one way or another, to the illustration of Jesus’s Passion. Some focus on those scenes where the Saviour faces an intolerable solitude, accentuating the contrast between his own purity and the ugliness of the men around him: Christ on the Mount of Olives, The Kiss of Judas, The Derision of Christ, Ecce Homo. These themes provoke cries of revolt from Dürer in the form of violent images that reflected his personal hopes and fears. Yet Dürer’s anguish also spoke for his entire era: in 1498, with Europe approaching the half-millennium, the German artist published his engravings of the Apocalypse, an attempt both to foretell and to curb the awful future that awaited.

Rembrandt, for his part (in addition to works drawn from his own daily life), etched many striking images in copper of Christ’s Passion. In his two Ecce Homo of 1636 and 1655, Jesus has been delivered up to the curiosity and rage of the crowd. In what must have been an expression of Rembrandt’s own feelings of guilt and communion with those people, the artist depicted himself among the throng witnessing the event. In Les Trois Croix (The Three Crosses), a total darkness gradually spreads across the picture as Rembrandt tweaked the composition state after state, so that, by the final version, only the body of the Crucified One has been illuminated. Likewise, in his Garden of Gethsemane, the darkness of dawn prevails except in the figure of Christ, bearing witness to Rembrandt’s absolute and passionate commitment to this most pathetic mystery of our Western civilisation.

Dürer and Rembrandt are unique in their constant expression of the idea of Christian sacrifice as it developed after the Reformation. Their Biblical narratives convey a profoundly human truth, with which everyone, even the illiterate, can identify. It is said that Pastor Cuendet frequently quoted the following passage from John in his sermons: "For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.” It seems clear that Cuendet’s sense of God’s love and sacrifice was borne equally in the masterpieces he collected.

Indeed, a true virtue of this collection lies in its remarkable thematic consistency. With the exception of two burins, La Mélancolie and the Portrait of Willibald Pirkheimer, all the prints by Dürer assembled by William Cuendet are Biblical narratives. Rembrandt, too, though perhaps less systematically, focused his energies on religious works. Cuendet, who was also a distinguished writer and a perceptive critic, discusses these works at length in a text wrote on his collection in 1947. It is hardly surprising, then, that many of Cuendet’s prints by Rembrandt illustrate Jesus’s eloquence and persuasiveness in addressing both the Temple and the popular crowds. Among these scriptural etchings, several of the most ambitious depict characters in the very act of speaking, and many illustrate passages in which speech is the central action. In these works, Rembrandt tends to show the protagonist as an orator hoping to captivate his audience, whether that audience be a single person (Eve persuading Adam to taste the forbidden fruit; Abraham explaining to his son the importance of his impending the sacrifice) or multiple people (Joseph recounting his dreams to his family; Jesus arguing with doctors of the Temple, speaking to his parents, addressing his disciples or the incredulous Pharisees, preaching to the crowd, etc.). It's easy to see how the pastor might have drawn inspiration for his Sunday sermons from these “speaking” images.

Like many in this country ("this mystical and dreamy little France" as Nerval calls it in the introduction to his Voyage en Orient), William Cuendet harbored a kind of restrained mistrust in the seductive colours and dazzling illusions of Italian painting. He clearly preferred the didactic narratives and honest representations made by northern engravers who, through the power of line, with only black and white, led the eye to inner metaphysical realities. It is not without reason, therefore, that the collector from Vaud, with the exception of certain irresistible plates such as La Mélancolie, declined to collect Dürer's secular repertoire, those enigmatic prints in which his subterranean and at times surreal imagination come to the surface. Yet it is precisely such exclusions that underline the unity and grandeur of this collection, reflecting both its objective quality and the personal commitment of a dedicated eye.

To be sure, collecting Dürer and Rembrandt was an easier undertaking in the first half of the twentieth century than it is today, when only museums and a few very wealthy individuals can purchase works that have become extremely rare. Driven by his passion, William Cuendet had the boldness and intelligence to start collecting at a very early age, as soon as he completed his studies, when these prints were not yet so expensive. With the help of his wife, he added to and embellished his collection over the years, habitually substituting a better print for a mediocre one, creating the kinds of opportunities that only dedicated amateurs know how to bring about. His son, Olivier Cuendet, recalls that the names of some of the greatest collectors, curators, art historians, publishers and dealers rustled around the house: "Gutekunst, Klipstein, de Bruyn, Lugt, Huyghes, Julliard, Visser't Hooft and later, Kornfeld, Decker...". By the start of the Second World War, Cuendet had aquired an exceptional body of prints, including Dürer's three Passions on wood and copper, as well as Rembrandt's masterpiece etchings The Three Crosses and The Hundred Guilder Coin. We can imagine that this collection was not made without effort. One wonders how much patience, skill and even sacrifice was required to amass, for instance, Cuendet’s full series of Dürer’s Life of the Virgin, comprising almost exclusively proofs before the text, which are rare and of the highest quality. At the origin of every true collection lies a history of unconditional, exclusive, and creative love.

It is striking to note that the two Lausanne collections that are now housed in the Musée Jenisch in Vevey complement each other perfectly. The first, from surgeon Dr. Pierre Decker, whose profession was to heal bodies, is full of prints that conveyed a full understanding of anatomy—the Dürer, as it were, of a scalpel-sharp burin. The second, from pastor William Cuendet, whose profession was to heal souls, was undergirded by its spiritual aspect. To be sure, Cuendet was highly sensitive to his prints’ craftsmanship, technique and aesthetic quality. His writings and lectures bear witness to his intimate knowledge of printmaking and the pleasure that every amateur can enjoy. ‘It is quite an art, learned little by little, he wrote, to know how to look at a beautiful, engraved sheet in all the right light, to extract its meaning and its moving secrets. You can recognise a true print-lover by some revealing signs: furtive gestures, very much his own, to feel the grain of the noble watermarked paper that supports a fine quality ink, certain flashes of the eye that caress the epidermis of a rare work, such affectations of indifference when the heart is in turmoil and, sometimes, the ostensible pleasure of an unreserved abandonment to enthusiasm in the face of the splendour of a perfect print’.

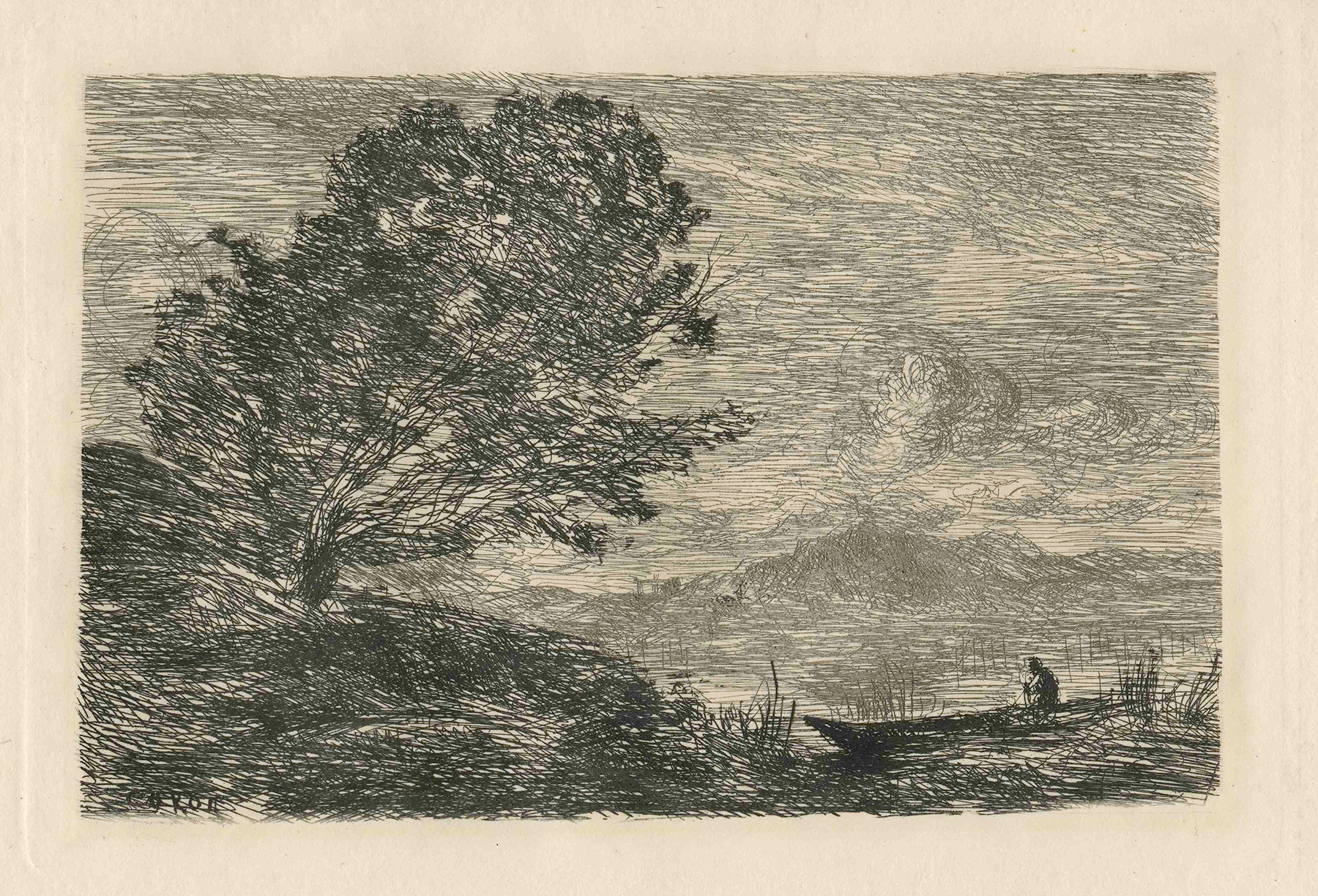

From 1921 to 1957, William Cuendet was a member of the Graphic Art Collection Committee at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, where he made friends with those who appreciated both his historical knowledge of printmaking and his interpretations of this rich and diverse art form. He died in 1958. In 1977, his widow and four children set up a foundation with a team of young artists working at the Atelier de Saint-Prex, whose mission was to ensure the continuity of his collection, to supplement it with new works and to perpetuate the spirit of curiosity and passion that had inspired Cuendet and his wife during their lifetime. Their children, Olivier and Madeleine in particular, were closely involved in the Foundation's activities. Over the years, they donated new works to the collection that had been acquired by their father the pastor—notably, a remarkable group of prints by Corot and a series of "tableaux en découpure" by Jean Huber.

Atelier de Saint-Prex and Pietro Sarto

What is known today as the Atelier de Saint-Prex began in 1968 in Villette (on the shores of Lake Geneva). In the words of its founder and main driving force, Pietro Sarto, the Atelier was ‘an undefined group of presses and printmakers, [...] a working tool that belongs to those who use it’. Some members of the L'Épreuve group, such as Albert-Edgar Yersin, Edmond Quinche, Marianne Décosterd and Pierre Schopfer, worked in this first creative centre; they were soon joined by other artists, including Jean Lecoultre, Francine Simonin and Denise Voïta, and, later, Albert Chavaz and Pierre Tal Coat. Since 1971, the Atelier has been based in the village of Saint-Prex, in a house bought by Sarto, welcoming foreign artists who stay and work there, who bring to Saint-Prex their enthusiasm and knowledge and share their discoveries. Funding for the Atelier is generated by publishing collaborations with editors, notably Gonin in Lausanne and Edwin Engelberts in Geneva. This open, generous house is above all a place where artists, dealers, collectors, curators, poets and lovers of art meet and exchange ideas. In the mid-1970s, these encounters gave rise to the idea of creating a Foundation that would consolidate that energy and spirit in the canton of Vaud. With the heirs of the pastor-collector William Cuendet, in 1977 they created the Fondation William Cuendet & Atelier de Saint-Prex. Since then, a copy of every print made on the Atelier's presses has been generously donated to the Foundation, contributing to the daily enrichment of its expansive collection.

Pierre Schneider, known as Pietro Sarto, was born in Chiasso in 1930. After growing up in Ticino, he spent his youth in Neuchâtel and then Lausanne. From 1950 to 1959 he lived in Paris, where he studied engraving with Albert Flocon and Johnny Friedlaender. On his return to Switzerland, he set up a series of intaglio workshops, where, alongside his work as a painter, he also worked intensively as a publisher. His first solo exhibition was in Lausanne in 1958. In 1976, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne exhibited his work alongside that of his friend Jean Lecoultre in an exhibition entitled “Curriculum Vitae.” In 1986, the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon held a retrospective of his work. His art is regularly shown at the Galerie L'Entracte in Lausanne and the Galerie Benador in Geneva. The Catalogue raisonné of his prints was published in 1993. In 2000, a retrospective was organised at the Fondation de l'Hermitage in Lausanne, and in 2004-2005, an exhibition entitled "La gravure en noir et blanc" was presented at the Musée Jenisch in Vevey. In 2012, La Bibliothèque des Arts published a monograph on Pietro Sarto, with texts by Florian Rodari, Laurence Chauvy and Pierre Darier. In 2022, the Musée Jenisch Vevey and the Villa dei Cedri in Bellinzona mounted an exhibition devoted to his work.

Pietro Sarto

Pietro Sarto often declares that printmaking is not separate activity, but rather a crucial aspect of his larger artistic vision. To say that Sarto has flaunted the so-called rules and traditions of this artform would be an understatement. For one, he often declines to print his plates in the traditional large number of copies. Similarly, he refuses to limit himself to a single technique, instead using as many as are necessary, however unorthodox or unexpected, to serve his vision. A close look at one of his copper plates shows what a "night's work" the material is subjected to before delivers its message to the page. In Sarto's hands, the copper plate is a mirror of melancholy, conducive to meditation and self-reflection. Early on, the painter-printmaker became interested in the process of developing states of a composition, offering him the chance to prolong and develop his work over time, as well as the opportunity to stop that process at any moment, capturing for posterity a fleeting stage of that ongoing metamorphosis. Sarto would use this extended process to deepen his vision, delve into the depths of an evolving image, and to mingle with its flow.

It is true that Sarto’s prints rarely express an assured sense of conclusion. Indeed, they remain works in progress, works with open futures, whose next direction is always uncertain. As such, Sarto might freely continue with oil on canvas what he started on the plate. Conversely, he might jumpstart a stalled painting by re-interpreting its composition in the brutality of acid. In this sense, etching, and especially aquatint, which Sarto favors, is a medium whose sense of surprise is crucial. The fluid transparencies that characterise aquatint call out for colour. The vapours and grains that it offers, more so than the hard line of engraving, give his tones and values a sensitive, tactile presence that aligns them closely with painting.

In Pietro Sarto's prints we often feel a vertiginous sense of falling, of being swallowed up by emptiness—as if we were a hang-glider in the open skies, or a sailor on the high seas. In his etchings, this sense of dissolution is accentuated by image which seem to lose all solidity and permanence, as if floating in a suspended space. Without context or visual reference, Sarto’s work becomes temporally indistinct, as if identifying with wind or wave—or, better yet, that mixture of air and water, the cloud. This, indeed, is the omnipresent, obsessive theme of Sarto’s visual poetics.

Gérard de Palézieux's legacy

Closely involved in the Fondation William Cuendet & Atelier de Saint-Prex since its birth, the painter-engraver Gérard de Palézieux (1919-2012) was a crucial figure in expanding its collections through several donations and bequests. An artist who was himself captivated by the light of Venice, Palézieux amassed for himself an exceptional collection of etchings by Canaletto, the Tiepolos, and several other printmakers who were active in La Serenissima. A great lover of landscapes, he painted and engraved his own views of the countryside and amassed a rich collection of etchings by Claude Lorrain and other famous practitioners of the genre. Later still, personal research led him to Degas's experiments with copper and monotype. A faithful supporter of the Fondation William Cuendet & Atelier de Saint-Prex, upon his death he bequeathed to it his own oeuvre, comprising several thousand prints and drawings, as well as his significant collection of prints by the masters he admired, such as Pissarro, Bonnard, Vuillard, Ker-Xavier Roussel and Picasso (as represented by the latter’s Saltimbanques series).

Gérard de Palézieux (1919-2012)

Born into a cultured family, Gérard de Palézieux began a traditional classical education, but at the age of sixteen he pivoted to enroll at the École des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne. There he took classes with Casimir Reymond and Henry Bischoff while benefitting from the advice of his friend Charles Chinet. Unsatisfied with the school's teaching, however, Palézieux looked to museums and books for new models of artistic excellence. In 1939, an administrative error allowed him to spend the first years of World War II in Florence, where he was introduced to Renaissance art and discovered the Tuscan landscape. There he frequented the studio of the Trovarelli brothers, who were custodians of all sorts of secret and nearly lost techniques. Palézieux would forever benefit from his time in Florence, and from those discussions, both technical and aesthetic, that took place in this small cenacle. In Florence Palézieux also discovered the paintings of Giorgio Morandi, whom he would later visit in Bologna.

After returning to Switzerland in 1943, Palézieux settled in a small vineyard house near Sierre. For the rest of his life he would remain in the Valais, whose landscapes became one of the main subjects of his painting, except for regular travel to Italy—to Rome and the surrounding area, to Tuscany, and then to the Marche, where he made paintings in oil and tempera. In 1947 he developed an abiding passion for etching. From the 1960s onwards, he lived in the Drôme, near Grignan, where his friend the poet Philippe Jaccottet had settled. His washes, drawings and etchings calmly depict this landscape, its architectural rhythms bathed in a quivering light. Palézieux’s classical art, in contact with the traditions of the past, found its moment of equilibrium.

In the mid-1960s, prompted by his friend the painter Albert Chavaz, he turned to watercolour, a faster, more fluid technique that he experimented with during stays in Morocco and Provence. Palézieux’s adoption of watercolour coincided with his discovery of Venice, which he visited regularly from then on. In Venice his art gained a newfound freedom, and his etchings were transformed by his use of aquatint or soft varnish to obtain the effects of light and transparency that are reminiscent of watercolour.

From his artistic beginnings, Palézieux's vocation was to represent, as closely as possible, his feelings for the spectacle of nature—whether landscapes, interiors, objects, flowers or fruit. Unusually for his time, which was dominated by those who questioned the value of representation and even art itself, Palézieux was immune to fashion, persevering boldly in his quest to translate the world as he felt it. As an artist, he strove foremost to render the vibration of light, to capture the tonal subtleties of the seasons he endured and countries he crossed, whether towns or countryside, mountains or riverbanks. That vision was closely linked to his material research, particularly his use of old paper, which bear the annotations of prior uses and the traces of their age. These various factors gave his images the impression of an artist who was increasingly attentive to the passage of time.

In addition to his independent studio practice, Palézieux was active as an engraver for various publishing initiatives. He illustrated, albeit very freely, works of poetry by his friends Gustave Roud, Philippe Jaccottet, Julien Gracq and Maurice Chappaz; these poets were among the first to acknowledge the importance of Palézieux’s art. In 1993, a major monograph on Palézieux was published by Éditions d'Art, Albert Skira Genève, with essays by Yves Bonnefoy and Florian Rodari. Numerous exhibitions have been devoted to his art, most notably at the Musée Jenisch in Vevey in 1989 and at the Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam in 2000. In 2019, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of his birth, a retrospective exhibition was organised by the Fondation Custodia and the Fondation William Cuendet & Atelier de Saint-Prex, first in Paris in autumn 2019, then at the Musée Jenisch Vevey in spring 2020. To mark that occasion, a 4-volume catalogue of his works on paper was published in Milan by 5 Continents Editions.