Collection

Techniques and media

-

-

Wood engraving (xylography)

-

Etching

-

Soft varnish

-

The glass plate

-

Drypoint

-

Lithography

-

The burin

-

Mezzotint (manière noire)

-

Aquatint

-

Photogravure

-

Media

Attempt to define a Print

A print is an image that can be reproduced from a printing element or matrix- such as an engraved wood block or metal plate - which, when inked, transfers its image onto a sheet of paper or another flexible material. Printing the same image in multiple copies, which varies according to the artist’s needs, is referred to as an edition. A proof is a printed impression taken from the matrix, whether during its development or as part of an edition. There can sometimes be variations between proofs from the same edition. These differences may result from variations in the ink, wiping, paper, or the pressure applied by the press. The printmaker may also choose - or be required - to rework the matrix, retouching details, adding elements, or enhancing certain effects. These changes, as they appear in the print, are called states.

Wood engraving (xylography)

The oldest engraving technique uses wood as its base material. The engraver begins by sketching the main lines of his design onto a wooden block, then uses tools like gouges, penknives or chisels to hollow out the block, leaving the drawn lines or flat empty spaces raised in relief. This process is called taille d'épargne (literally, “saving cut”), because the tool spares the drawn areas - unlike intaglio engraving, where the inked lines are incised into the surface. Once the image is clearly defined, the printer uses a roller or pad to apply greasy ink to the raised surfaces of the matrix. A sheet of paper is then carefully placed on top, and pressure is applied - either with a vertical press or by rubbing the back of the sheet with a spoon - to transfer the inked image. Due to the fragility of the material, xylography often results in bold contrasts. Yet in the hands of master artist - such as Dürer in his Passion series or Vallotton in his chronicles of everyday life - this technique produces direct, powerful images that quickly resonate with viewers.

Etching

Etching, a technique developed in the early 17th century, can be used on matrices of iron, brass, zinc or steel. However, copper is the metal most often chosen by engravers, admired for its beautiful reddish-orange hue. The process begins with the artist coating a perfectly clean and flattened metal plate with a thin layer of varnish, applied with a brush or pad. This layer hardens slightly as it dries. Using a pointed tool, the artist then draws into the varnish, exposing the metal beneath wherever the tool touches. Next, with the back of the plate protected, it is immersed in an acid bath. The acid etches into the exposed areas, while the varnished sections remain untouched. Depending on the type of acid used - nitric acid or ferric perchloride - the etched lines may appear broader and softer or sharp and deep. The duration and strength of the acid bath are also adjusted to achieve the desired effects.

Once etching is complete, the varnish is removed, and the plate is thoroughly cleaned. Ink is applied to the plate, filling the etched grooves, and then carefully wiped by hand to clean the surface. A dampened sheet of paper is laid over the plate, and both are run through a press. With careful adjustments to pressure and ink, the image transfers from the etched recesses, resulting in a richly textured print.

Soft varnish

In this technique, instead of applying a hard varnish as in traditional etching, the engraver applies a soft varnish to the copper plate. This varnish, with a consistency similar to honey, is spread evenly across the plate’s surface. A sheet of paper - or another textured material used as a support - is then placed on top, and the artist draws on it with a pencil. When the sheet is removed, the varnish lifts off wherever the pressure of the drawing caused it to stick to the paper, exposing the metal beneath.

During the acid bath - which is usually brief - the acid bites into the areas left exposed, capturing even the slightest pressure from the drawing, down to the texture of the paper or fabric. This method was widely used to reproduce drawings, especially red chalk anatomical studies and the so-called three-pencil portraits that were fashionable in the 18th century.

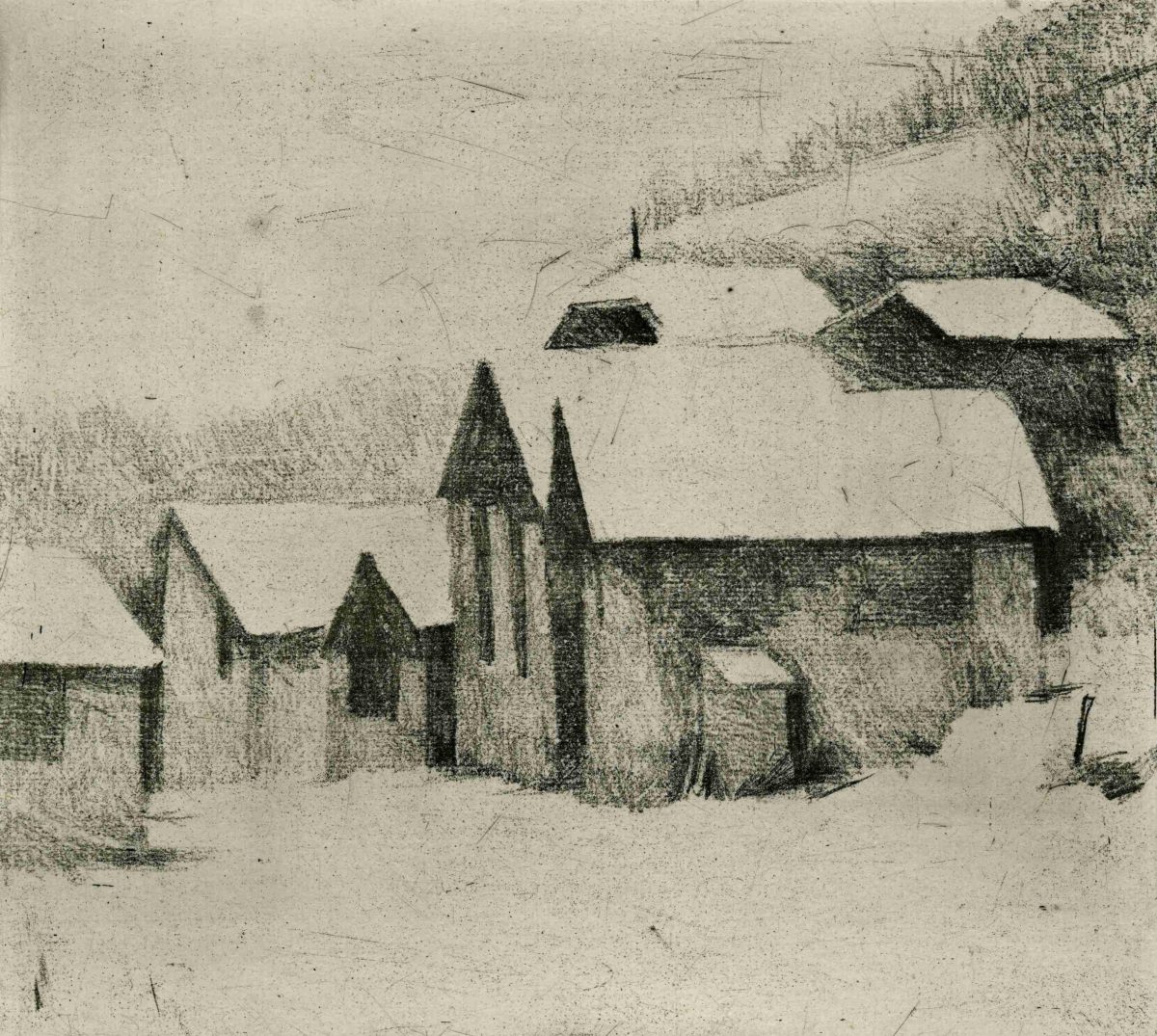

The glass plate

The glass plate technique emerged with the birth of photography and borrows several of its methods and materials. The artist begins by coating a translucent glass plate - of varying thickness - with a layer of collodion, which serves as both varnish and negative base. On this surface, the artist draws with a dry-point pen or brush. Once the 'matrix' is complete, it is placed against photosensitive paper and exposed to light, allowing the drawn lines to be transferred. The resulting image will be extremely sharp and precise if the incised side of the glass touches the paper directly. If the glass is reversed, however, the image will become blurred due to the uneven thickness of the glass through which the light must pass before reaching the paper.

Because the fragile glass is not subjected to pressure from rollers, it acts as a negative rather than a traditional printing plate, and the image can be reproduced as many times as needed. In France, artists of the Barbizon School were especially intrigued by this innovative process, which often yielded unpredictable but light-sensitive results - ideal for capturing the atmospheric qualities of their landscape scenes. The Cuendet collection includes most of the freehand glass plate drawings that Corot produced between 1853 and 1873 using this technique, which would later fascinate contemporary printmaker Pierre Schopfer over a century later.

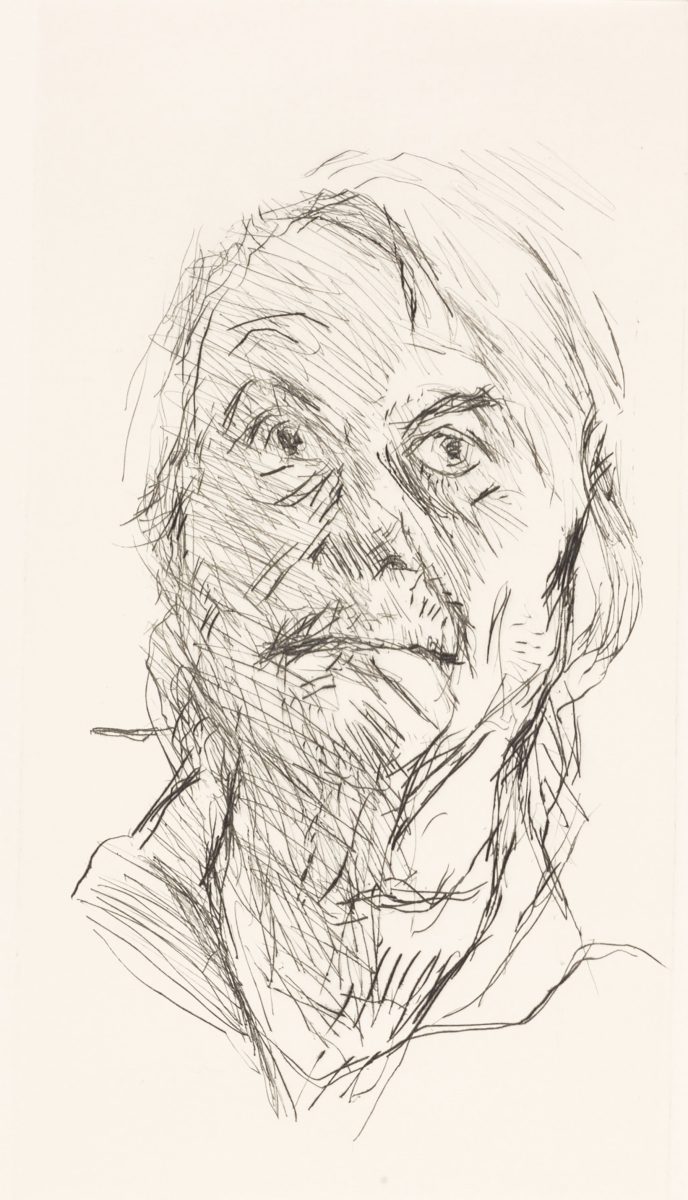

Drypoint

Whereas using a burin demands precise control and a clear vision of the final image, drypoint allows for more spontaneity. Any pointed object - needle, awl, nail, scraper or knife - can be used to scratch, dig or puncture the copper plate directly. Because it begins directly on the matrix, drypoint is often used to retouch or enhance etched plates, particularly to strengthen weak lines or to deepen shadows. As the artist scratches the copper surface, the tool creates small metal burrs, or barbs, which trap ink and transfer lines. By layering these scratches in multiple directions, the engraver can build up an area of continuous shadow - an effect used masterfully by Rembrandt in his dramatic chiaroscuro compositions. However, there is a drawback: these delicate barbs are easily flattened by repeated passes through the press, so only the earliest proofs retain the full richness of the original line. This problem wasn’t resolved until the 19th century, when electroplating was introduced. In this process, a think layer of iron was deposited over the copper surface, making it far more durable and and preserving the image across a larger print run.

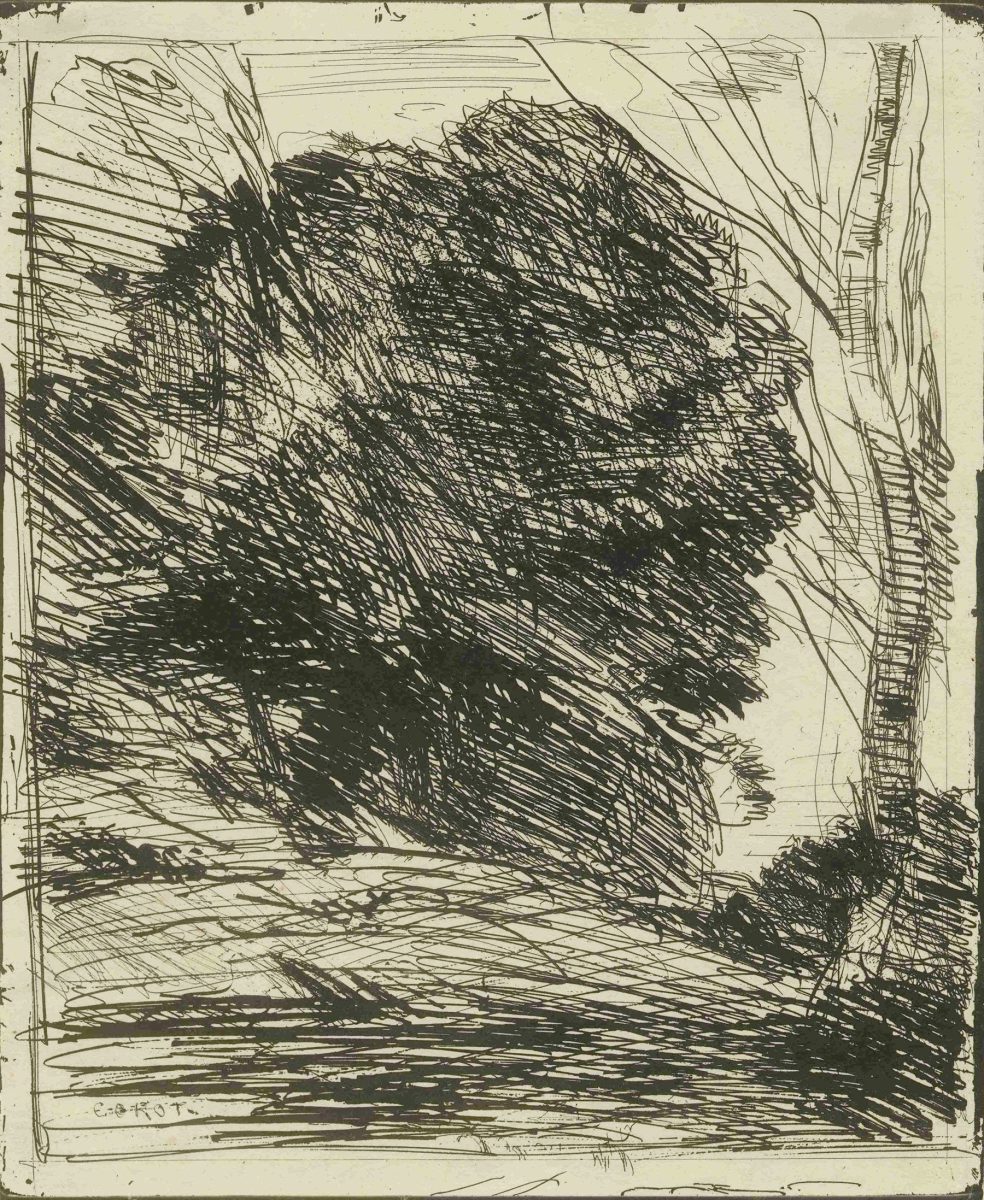

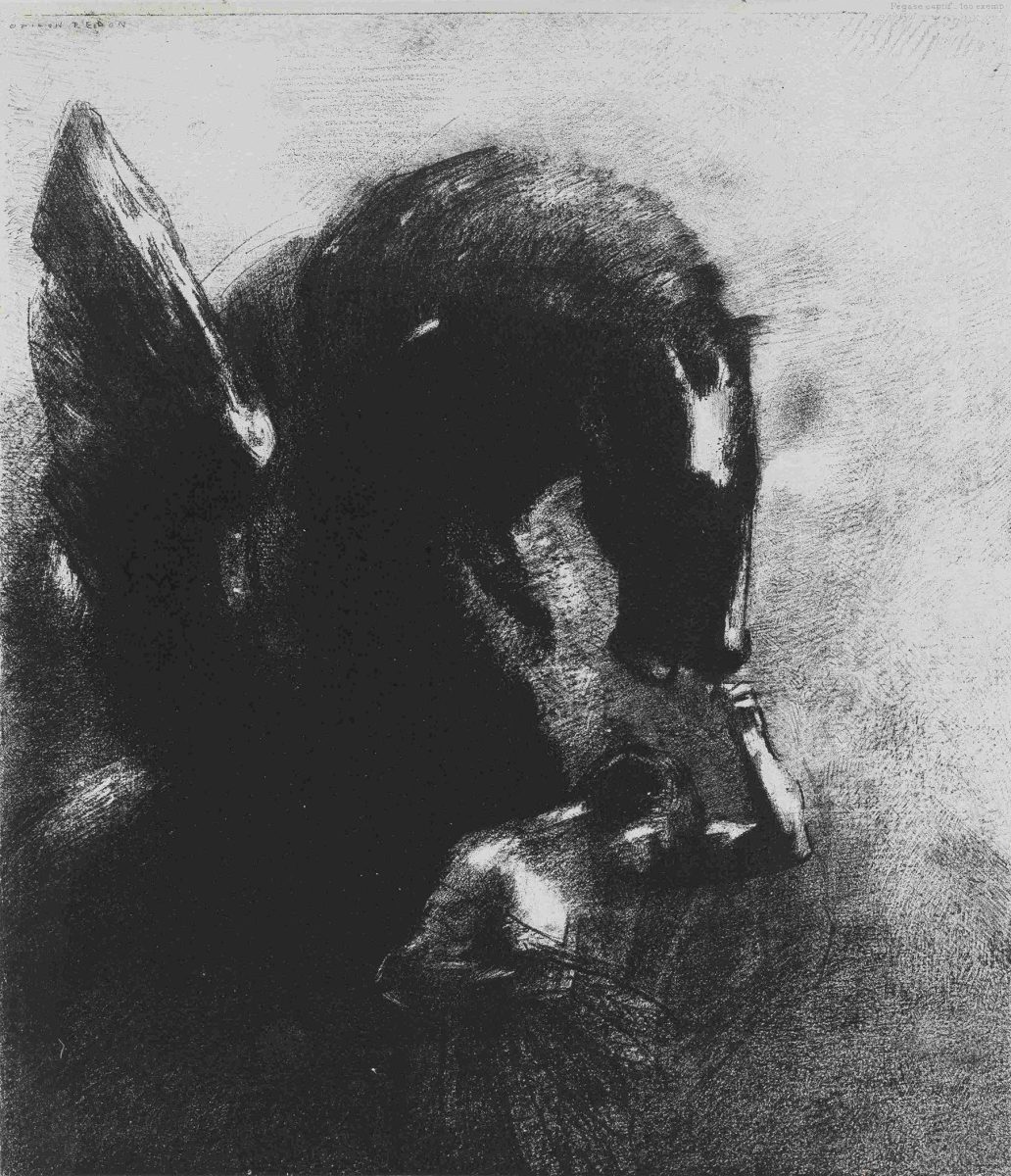

Lithography

Unlike engraving or etching, lithography involves no grooves or raised surfaces. Relying on the natural repulsion between water and grease, lithography is closer to drawing than to traditional printmaking. Invented by Aloys Senefelder in the late 18th century, the technique’s major advantage - aside from enabling large, industrial print runs - is that it allows the artist to draw directly on the grained surface of the stone with great freedom. Technical advances eventually allowed for the use of colour and washes, as well as larger formats. Artists could now produce bold, expressive works for advertising and street display. Toulouse-Lautrec and Bonnard both demonstrated their brilliance in the poster format, while Redon created haunting visions in crayon, which ranged tonally from pale grays to deep blacks. The Cuendet collection also includes work by late 19th century artists such as Bresdin, Vuillard and Xavier K. Roussel. Artists like Pietro Sarto and Edmond Quinche, who led the Atelier de Saint-Prex lithography studio for many years - pushed the technique further with their continuous experimentation and curiosity.

The burin

This technique, directly descended from niello work of Renaissance goldsmiths, involves engraving into copper with a sharp, V-shaped tool known as a burin. Held firmly in the palm, the burin is carefully pushed into the metal to carve out lines that will later hold ink. The process is demanding: it requires patience, concentration, and physical control. To build the image, the engraver must vary the depth and spacing of the lines, weaving together fine networks and textures, adjusting their direction to mimic lights and surfaces. In this way, burin engraving becomes a complex visual language - one capable of astonishing subtlety. Dürer's Melancholy of 1514 remains its most iconic masterpiece. For two centuries, before the rise of etching, burin was the primary tool for spreading knowledge and imagery across Europe - illustrating discoveries, documenting journeys, and serving political and religious authorities. The technique reached its peak in 17th-century France, where engravers like Claude Mellan (1598-1688) and Robert Nanteuil (1623-1678) produced psychologically rich and masterfully intricate portraits.

Mezzotint (manière noire)

This technique, developed in Germany in the mid-17th century, is a form of direct engraving on copper that works in reverse to most traditional methods. It begins with covering the entire plate in a dense field of tiny pits, whose raised edges form burrs that hold ink. This initial step entails a meticulous and laborious preparation. Using a tool with a curved steel blade covered in fine teeth - called a “rocker” or “cradle” - the engraver (or often an assistant) rocks it gently back and forth, in every direction, across the surface of the copper. This step is repeated multiple times until a uniformly, densely grained texture is achieved. If printed at this stage, the plate would produce a rich, velvety black.

Once this dark base is prepared, the artist then begins to reveal an image by smoothing the surface with a burnisher. Depending on how much the burrs are flattened, lighter tones begin to emerge. By skillfully varying the degree of polishing, the artist can achieve a wide range of values - from dark grey to light grey, and up to pure white, obtained by scraping the plate smooth. This capacity to render the full tonal scale, and especially the mid-tones, is what gives the technique its name: mezzotint, or “half-tone.” Particularly responsive to the subtleties of texture and light, mezzotint was highly valued in England, where it became popular for rendering chiaroscuro portraits in which a soft glow illuminated skin, fabrics and wigs. The technique’s subtle gradations of value even led to the development of three-colour engraving in the late 17th century. The French artist Gautier-Dagoty used it to create early anatomical illustrations, some of which - like the famed Ange anatomique - are held in the Cuendet collection.

Aquatint

Aquatint, a descendent of traditional etching, is an acid-based technique that requires no drawing tool. Though it first appeared in the mid-17th century, it was perfected in 1768 by Jean-Baptiste Le Prince. Often referred to as engraving in the manner of wash (gravure en manière de lavis), it excels at recreating the delicate tonal transitions typical of brush and ink work.

The process begins with the careful application of powdered rosin -a natural resin - onto a finely sanded and cleaned copper plate. This dusting typically takes place inside a “grain box,” where the particles are lifted into the air and allowed to settle evenly over the plate’s surface. The plate is then gently heated so the grains adhere. When the plate is submerged in an acid bath, the acid only bites into the tiny spaces between the particles, leaving the grains intact.

By adjusting the coarseness of the grain and the duration of the acid bath - usually with ferric chloride - the artist can control the density and texture of the resulting tones. At its most refined, aquatint can simulate a fluid wash; at its roughest, it mimics the grain of a graphite drawing. In the 18th century, this method was widely used to reproduce the elegant compositions of fashionable painters for a public hungry for graceful, decorative scenes.

A few decades later, Goya took up the technique with striking originality. Favoring a bold, gritty grain, he harnessed aquatint’s expressive potential to create images in which light seems to take on a physical presence. With its ability to produce broad, modulated areas of tone, aquatint remains a cornerstone of painter-printmakers’ practice to this day.

Photogravure

It is sometimes overlooked that the origins of photography lie as much with engravers as with chemists. For the earliest inventors, the challenge of fixing an image soon turned into a search for a medium that could withstand both heavy printing and the test of time. Among the many solutions, photogravure emerged as both the most reliable and the most visually compelling. This process, which allows for the printing of an extraordinary range of tones - from the deepest blacks to the palest greys - draws directly on aquatint’s granular structure. By transferring a photographic image onto a plate prepared with aquatint, the technique introduces a tactile surface that enhances the illusion of depth, rendering the effects of light with remarkable dimensionality. Though photogravure was eventually eclipsed by more cost-effective methods, its subtlety and richness continued to attract artists and photographers alike - those who sought not just to reproduce images, but to give them a particular presence, a printmaker’s signature touch.

Media

In the history of printmaking, technical innovations have primarily responded to the ever-increasing demand for the widespread dissemination of written words - and for those words’ graphic illustration. All these innovations, however, are based upon a list of both conceptual and physical aspects that have allowed us to arrive at some (hopefully) satisfactory definitions for printmaking.

A print is an image that can be reproduced identically from a printing element or matrix, such as a wooden block, an engraved metal plate, or even a stone. After being covered in ink, this matrix then transfers an image to a sheet of paper (or any other suitably flexible material) when it is pressed to said material by a mechanical press or other means

Before a first proof is produced, numerous materials, processes and skilled individuals are involved in this production. Since the print is intended for a public audience, it requires the collaboration of a publisher - either the artist himself or a company experienced in the field. Before the artist begins his work, he must select the material on which his image will be engraved. Depending on availability and the artist’s preferences, this matrix could be made of wood (preferably from a fruit tree), metals such as copper (and less commonly iron, zinc, or tin), stone (especially very fine-grained limestone), or even Plexiglas or linoleum.

Next comes the choice of paper, which varies according to the artist’s or publisher’s preferences. This paper can be flexible or sturdy, thin or thick, yielding to pressure in different ways. Ink plays a crucial role; its various qualities significantly affect the resulting print, hinging on such as its binder, ingredients, drying time, and material body and tack.

A wide array of tools is necessary - tools for digging, scraping, scratching, skimming, crushing, removing, and smoothing. Additionally, a press must be carefully calibrated to suit the matrix, ensuring both precision in the line work and the faithful transfer of values in the ink.

Human skill is, of course, paramount in this process. Some artists, like Rembrandt, personally oversee each stage of production. More frequently, however, an organised workshop manages the print edition. It is quite common for the artist's drawing to be traced onto the matrix by a craftsman. Other workers might be responsible for carving the lines, preparing the varnishes, measuring acid content and the soaking the paper in preparation for printing. Some may cut and moisten the paper sheets, while others focus on retouching or specialise in specific areas such as figures, borders, frames or lettering.

If the printer is working with woodcut, the workshop will secure the wooden block under the press to create a complete print. In the case of intaglio, the plate must be placed carefully between felts, ensuring that the edges are respected before passing it under the rollers of the machine, which has been precisely calculated for pressure. Once the plate is "ready for printing", the desired number of copies is produced. Each sheet emerging from the press is laid flat and, if necessary, folded before being bound into a volume or offered as a numbered edition.