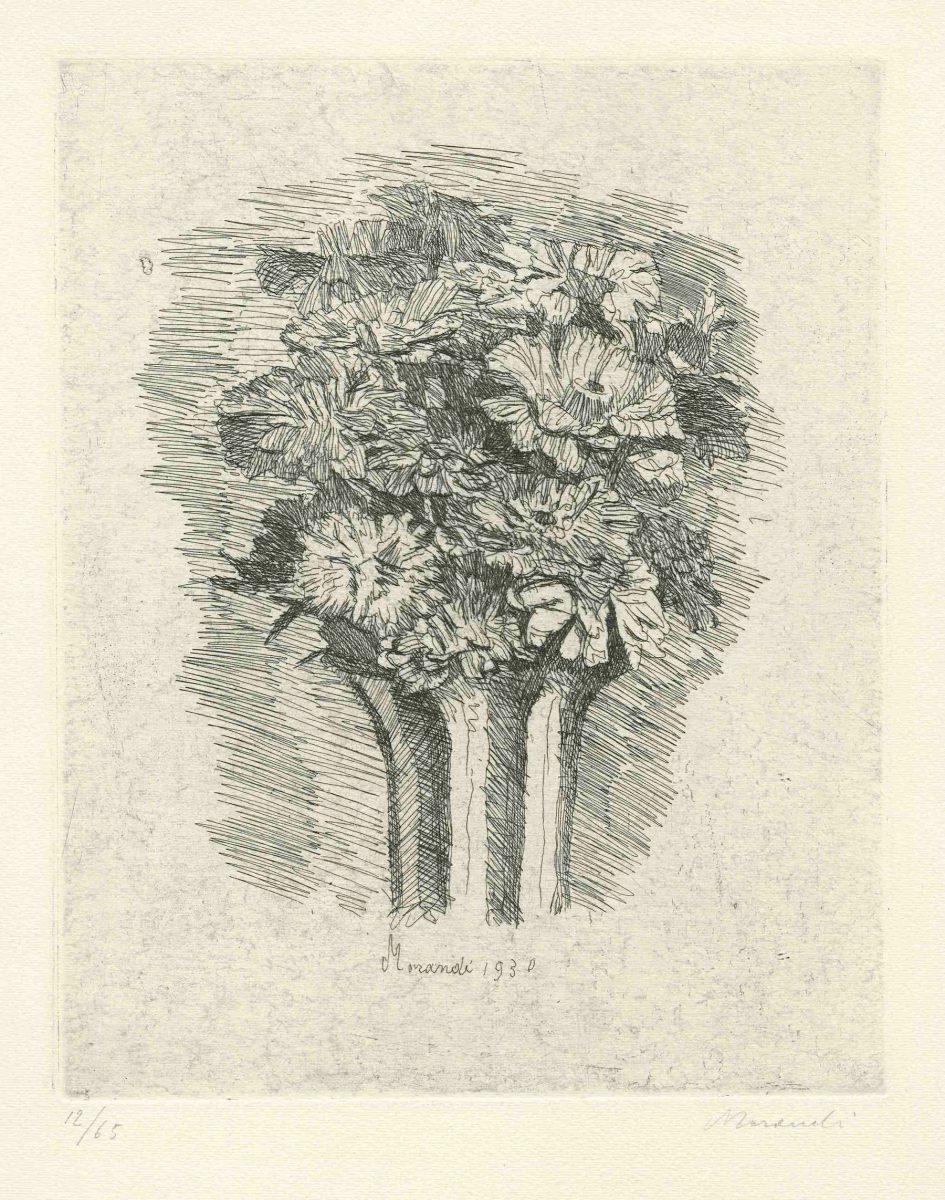

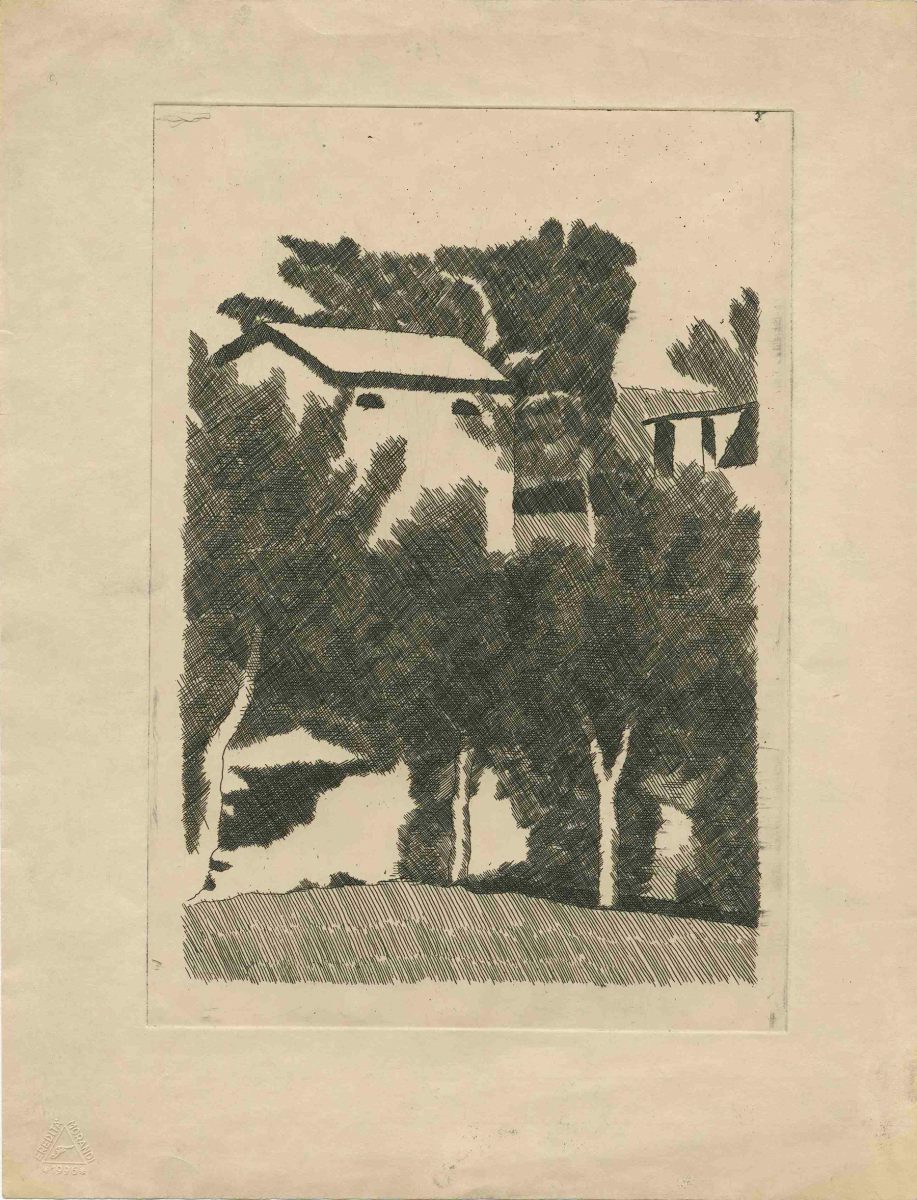

The collection of the Fondation William Cuendet & Atelier de Saint-Prex currently possesses four prints and one oil painting on canvas by Giorgio Morandi. All these works came to the collection from the bequest of Gérard de Palézieux, who met the painter in Bologna in 1953 and maintained regular contact with him until Morandi’s death in 1964. The Bolognese artist's sober yet quietly powerful style had a strong influence on Palézieux early on, both in his choice of themes - still lifes and landscapes - and in the linework of his etched copperplates.

The Italian painter and printmaker Giorgio Morandi occupies a special place in the history of 20th-century art, with a body of work that is as distinct as it is fascinating. Born in Bologna in 1890, Morandi studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in his hometown from 1907 to 1913. Upon the death of his father in 1909, he moved with his mother and sisters to a house on Bologna’s via Fondazza, where he would live and work devotedly until his death in 1964. During his youth, he carefully studied Giotto, Masaccio, Uccello and other figures from the great tradition of Italian art, while also keeping tabs on the ongoing developments in modern art. Morandi showed an early interest in Futurism, Cubism and metaphysical painting, but he developed his greatest admiration for Cézanne, whose paintings would deeply influence his own approach. From the outset, Morandi's work was characterised by a sober palette of nuanced chromatic grays. With the exception of his landscapes (which are systematically devoid of human figures), the artist focused his attention on still life. To make these, Morandi placed, replaced, positioned and repositioned a handful of bottles, cans and jugs on his tabletop, working from observation. These humble objects became, in Morandi’s hands, deeply meditative architectures, which stand up with quiet strength against the disorder of time. He continued to work from these still lifes for several decades, producing what became an astonishing number of paintings and etchings. For a time, faced with financial difficulties, Morandi took on several teaching posts. Notably, he taught engraving techniques at the Bologna Academy of Fine Arts. It wasn't until after the Second World War that he finally gained a substantial recognition, which owed much to etchings. His 136 etchings depict the same subjects as his paintings, but their reduction of means—limited to only two tones, black and white—forced the artist to synthesise his language even further. Morandi’s visual syntax relies on artful spacing and simple crosshatchings to create light, which glides along his tabletop forms and lingers in their shadows.