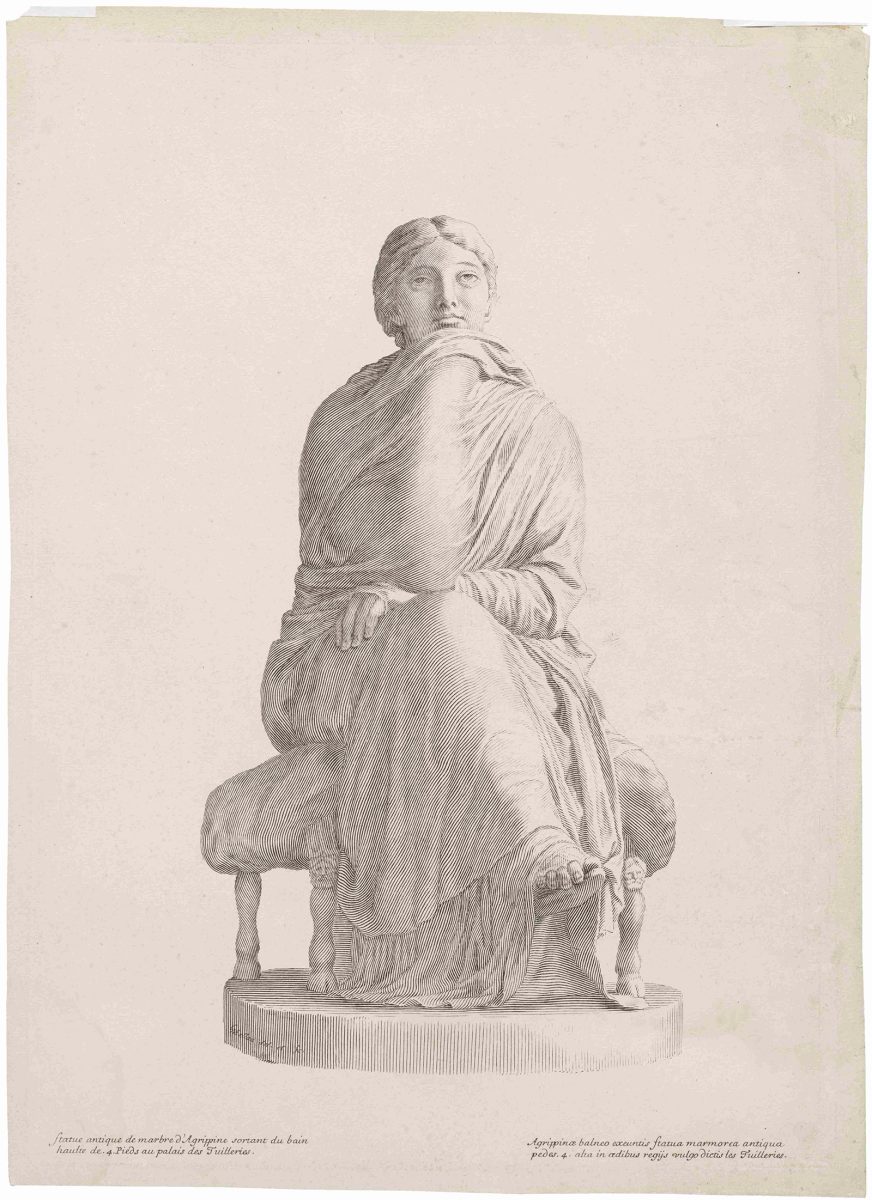

As a teacher, Albert-Edgard Yersin often spoke of Claude Mellan, an artist whose structural pictorial language fascinated his students. In Mellan’s virtuosic engravings, complex images are constructed with long contiguous lines, dispersing tone across the composition only through variations in the lines’ thickness and the spaces between them. These absorbing works were pored over by artists, and they were much admired by collectors. The Fondation William Cuendet & Atelier de Saint-Prex now holds more than 270 plates by Claude Mellan, most of which were donated by Isabelle and Jacques Treyvaud, including both portraits and religious subjects. Other plates, including his Self-Portrait (1635) and a copy of the remarkable Sainte Face (The Holy Face, 1649), come from the collection of Gérard de Palézieux, which was left with the Fondation in 2005 and entered its permanent collection in 2012. In 2016, the Fondation acquired fourteen plates from the series representing the statues of the Galleria Giustiniana del Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani, including a copy of the famous Agrippine sortant du bain, (Agrippina emerging from the bath 1640).

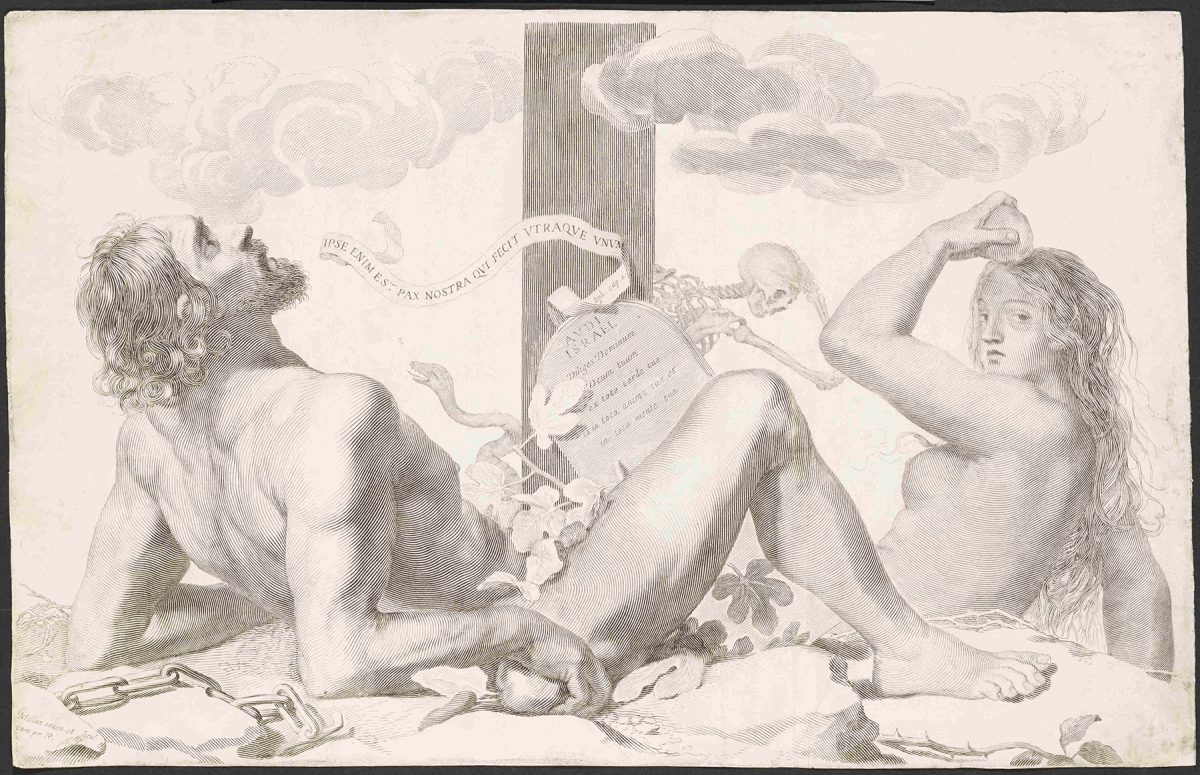

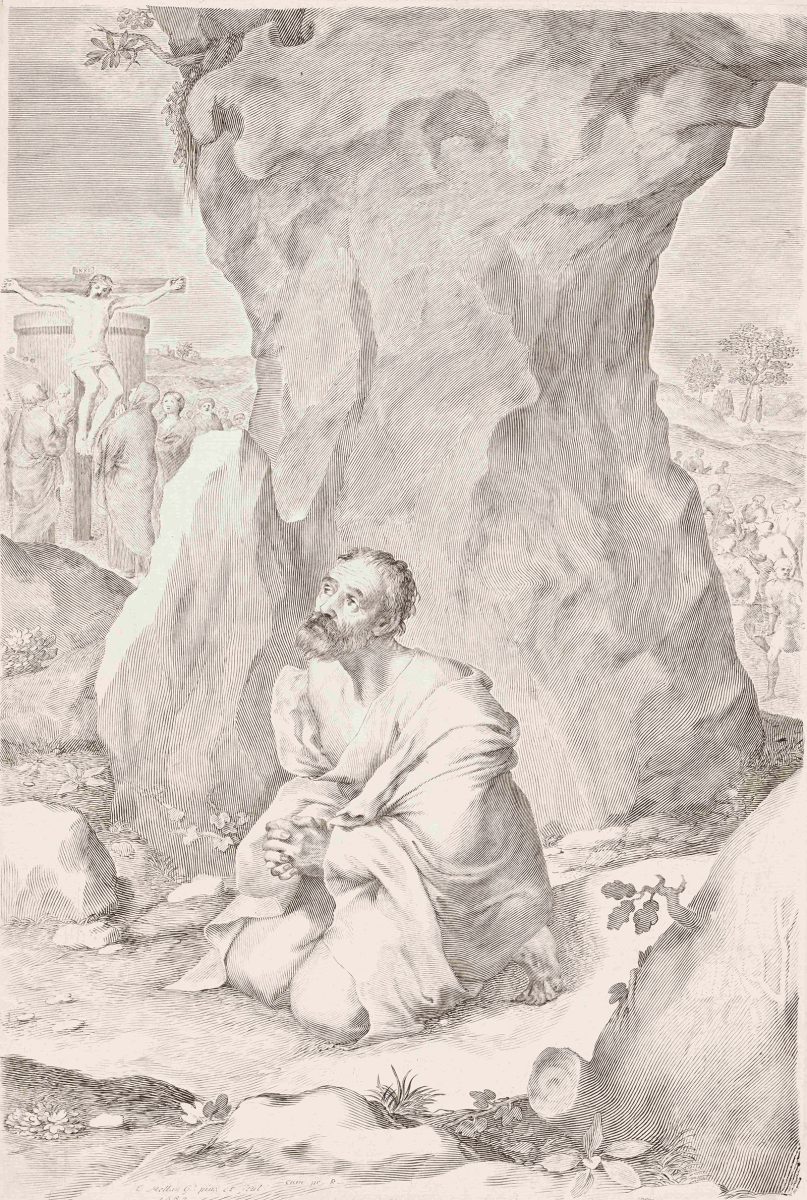

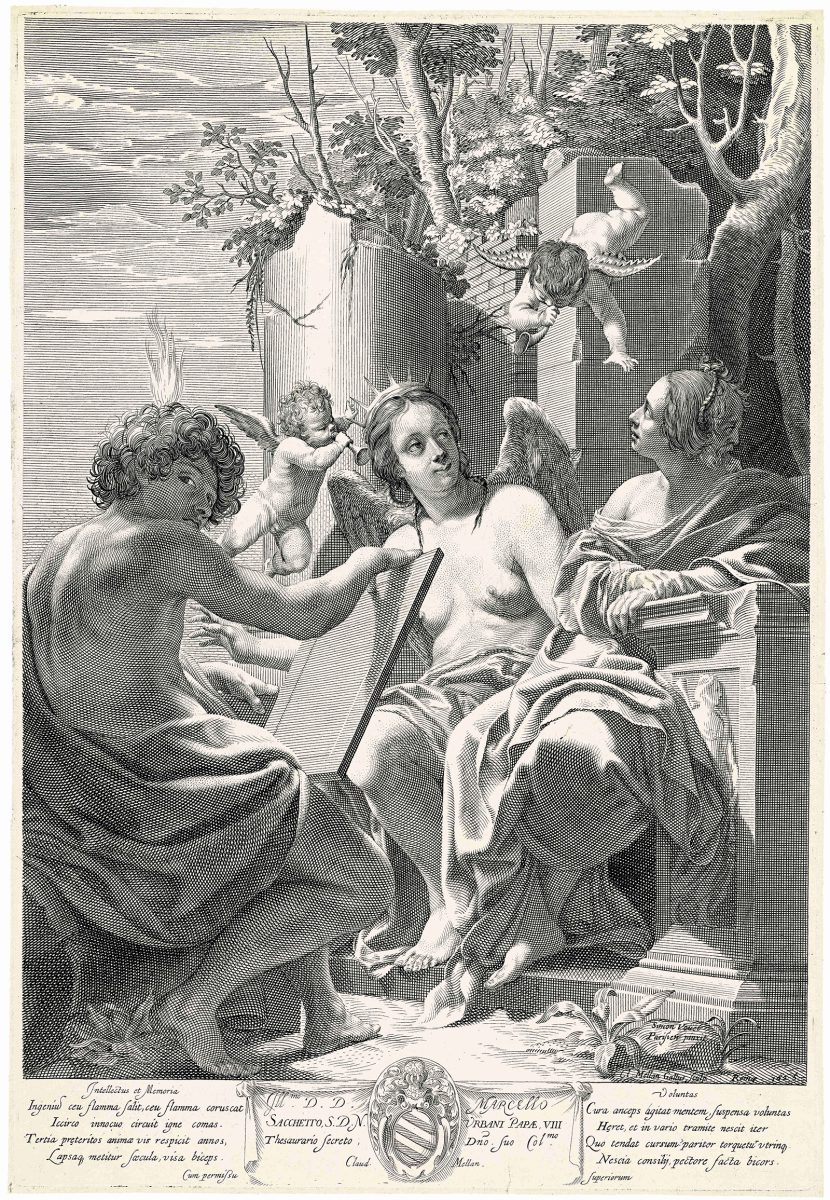

Claude Mellan (1598-1688) began his apprenticeship as an engraver in Paris in the late 1610s, a relatively inert period for printmaking in France. After setting up his workshop in the rue Saint-Jacques, his talent was quickly noticed by a wealthy scholar and collector from Aix, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc. It was undoubtedly thanks to the latter's support that Mellan was able to move to Rome in 1624, where he remained for twelve years. For Mellan, this period in Italy was a time of intense learning, first with engravers such as Francesco Villamena and Antonio Tempesta, then with great artists such as Bernini and the French painter Simon Vouet. In Rome, Mellan not only perfected his mastery of drawing and composition, but also began to socialise with the city’s intellectual and artistic elite, giving him the opportunity to paint many portraits. His engraving technique developed considerably, gradually giving rise to a highly personal syntax that was based on both a complex execution and a great economy of means. In these works, Mellan abandoned the repeated, short, cross-hatched strokes that are traditional in engraving, in favour of a system of long, contiguous lines. In Mellan’s innovative method, it is no longer the criss-crossing of strokes that determines the distribution of shadow and light, but rather the thickness of each line and that of the space left between them. On his return to France in the late 1630s, Mellan used his novel technique to create portraits of the scholars he met with, including Gassendi, La Mothe Le Vayer and Guez de Balzac. But it is in Mellan’s famous Sainte Face (1649) that his method is most strikingly demonstrated: here, the entire composition is created using a single, winding line, which spirals out from the tip of Christ's nose. A participant in engraving’s revival in the first half of the seventeenth century, Mellan was granted a permanent residence in the Louvre, and he received numerous commissions, including projects to make burin reproductions of antique statues in the royal collections. Towards the end of his life, he devoted a series of prints to the theme of Christ’s Passion, which, with their expression of both harmony and limpidity, fully justify Florian Rodari’s description of Mellan's art as a kind of "white engraving."