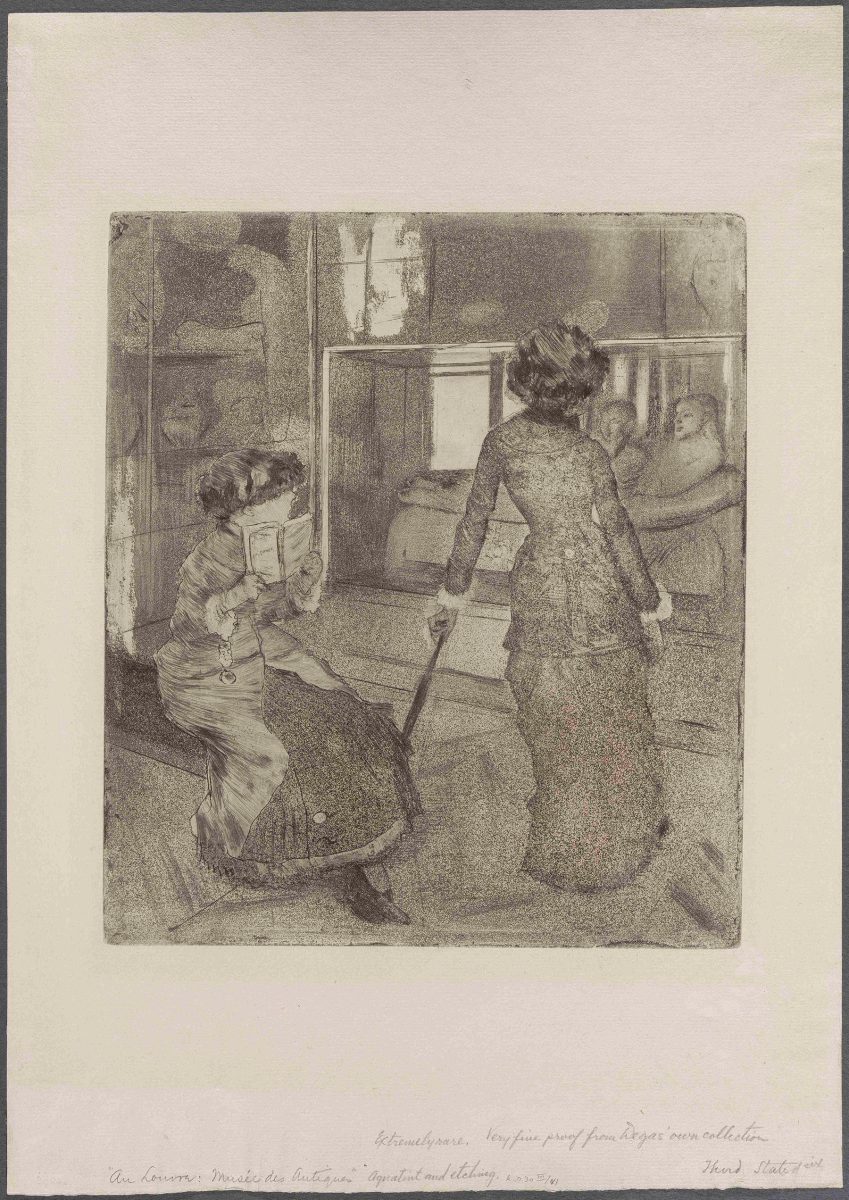

Like in any printmaking workshops, artists in the Atelier de Saint-Prex have always shared the secrets of their craft and discussed the great masterpieces of the past. Printmakers came together to deliberate on these emblematic images, hoping to solve their ineffable mysteries, unpack their processes and techniques, or merely admire them for their obvious beauty. Degas, who conducted intrepid experiments with plates, papers and inks, is one of the most studied of these master printmakers. Thanks to a bequest from Gérard de Palézieux, the Fondation William Cuendet & Atelier de Saint-Prex owns around fifteen examples of this “tinkering” genius, including a monotype and a remarkable etching entitled Mary Cassatt au Louvre, Musée des Antiques (ca. 1876).

Edgar Degas, one of the most influential figures in French art at the end of the 19th century, grew up in a bourgeois Parisian family. In 1855, after dropping out of law school, he began studying at the École des Beaux-Arts. A great admirer of Ingres, he immersed himself in the art of the great masters, copying their works in the Louvre and the Cabinet des Estampes. At the end of the 1850s, he travelled frequently to Italy to continue his study of the past. Then, in the early 1860s, he met Édouard Manet and turned to subjects inspired by contemporary life. Over the next few decades, Degas became one of the most important members of the Impressionist movement, although his fierce independence and his classicist bent set him somewhat apart from the rest of that group. Though the latter part of his career was marred by serious eyesight problems, Degas drew, painted and sculpted until his death in 1917.

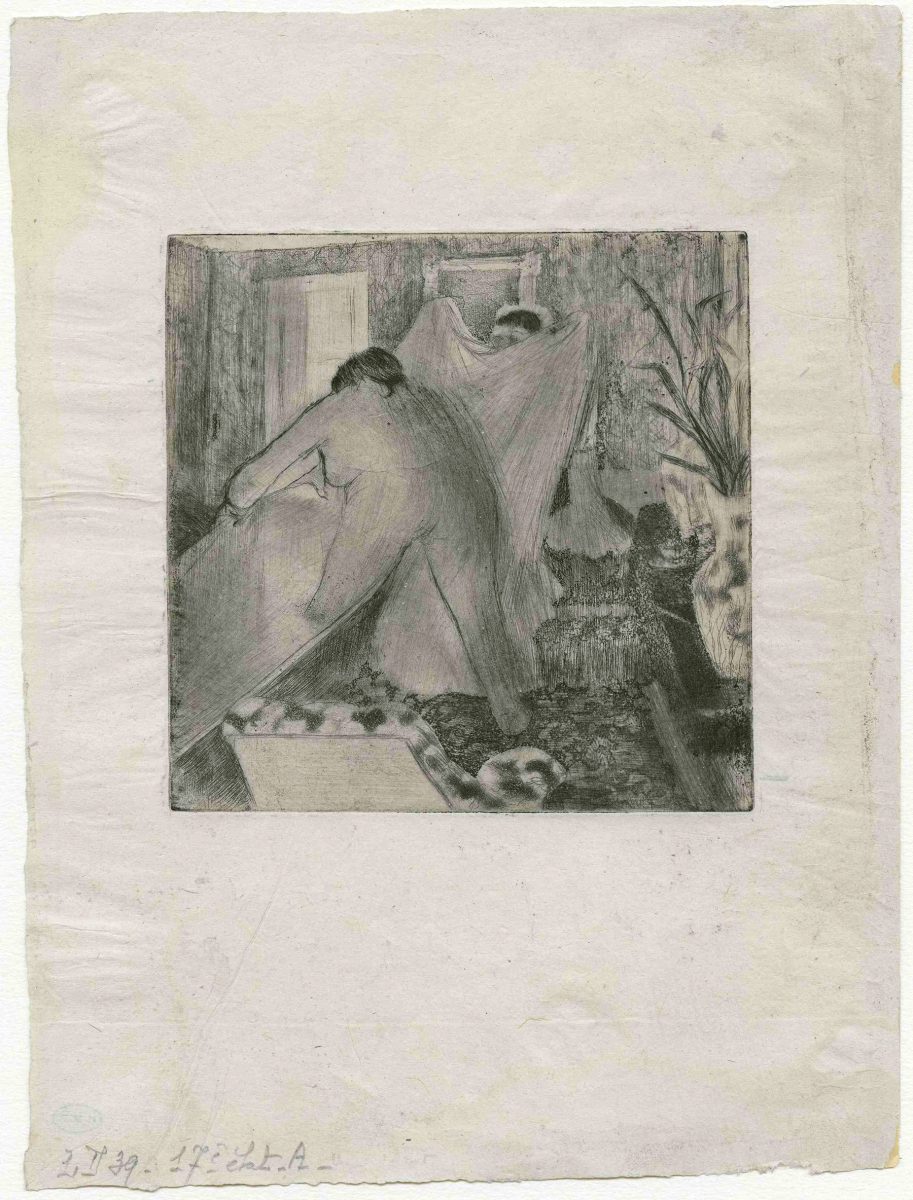

Degas, whose oeuvre of prints include 66 plates and more than 200 monotypes, was clearly one of the great painter-printers of his time. His work in etching dates back to 1856, making him a forerunner of the "revival" of this technique, which took off six years later with the creation of the Société des Aquafortistes. After a few attempts at the landscape, Degas produced a series of portraits in the style of Rembrandt, including a fine self-portrait (1857) that he probably realized in Rome. On his return to France, he achieved three remarkable portraits of Édouard Manet. After a long break from this practice, Degas returned to it in the second half of the 1870s, ushering in a period of particularly intense creativity, during which he produced some of his finest prints. These were technically experimental and aesthetically astonishing works: Degas relentlessly experimented with new process to find different textures, and he made passionate use of both lithography and the unusual monotype process. Learning about these mediums on the fly, as it were, Degas often worked through a great many versions of a given composition: Sortie du bain (Leaving the bath), for example, has a full twenty-two states (1879-1880). After the failure of a magazine project, Le jour et la nuit, Degas once again turned away from printmaking, but he returned to it at the beginning of the 1890s, ultimately producing an innovative series in lithograph of female nudes at their toilette.