Most of the artists working at the Atelier de Saint-Prex took a keen interest in the landscape genre. It is therefore not surprising to find in their collection a variety of printed landscapes by a number of masters from all centuries. Alongside prints by Corot and Bresdin, for instance, Gérard de Palézieux was particularly attracted to the etchings of Claude Lorrain, who achieved in his compositions an immaculate expression of light and balance. Over the years, while making his own landscape paintings, drawings and watercolours, Palézieux acquired an exceptional collection of around thirty compositions - many in several states - by the Rome-based Claude.

Claude Gellée, known by the French as "Le Lorrain" in reference to his home region, is considered by many to be the greatest landscape painter of the 17th century. Relatively little is known about his childhood and youth, but we do know that he left France in his early teens, at the turn of the century, for Rome, which was then the artistic capital of Europe. There Claude became the assistant of the Mannerist painter Agostino Tassi. Around 1620, he spent two years in Naples, where he continued his training. In 1625, Claude returned to Lorraine, but stayed for only two years before travelling again to Rome, where he set up his own studio. At this time, the genre of landscape was undergoing a profound transformation as a result of recent innovations by painters such as Annibal Carracci, Paul Bril and Nicolas Poussin. Claude took part in this ongoing tradition. Drawing his inspiration from the Roman countryside, which he travelled tirelessly, Claude produced ordered landscapes of great sensitivity and harmony, which were particularly innovative in their treatment of light. In 1633, he was admitted to the Accademia di San Luca, the main association of artists in Rome. From the 1630s onwards, he received commissions from important clients such as Pope Urban VIII and the King of Spain, Philip IV. Such was his success that forgeries of his work flooded the market, prompting Claude to draw up a detailed catalogue of his oeuvre, the Liber Veritatis, in 1635. Over the following decades, and until his death in 1682, Claude Lorrain, who enjoyed a consistently high reputation and never wanted for commissions, continued to develop his style, giving rise to the melancholy, serene landscapes for which he remains renowned.

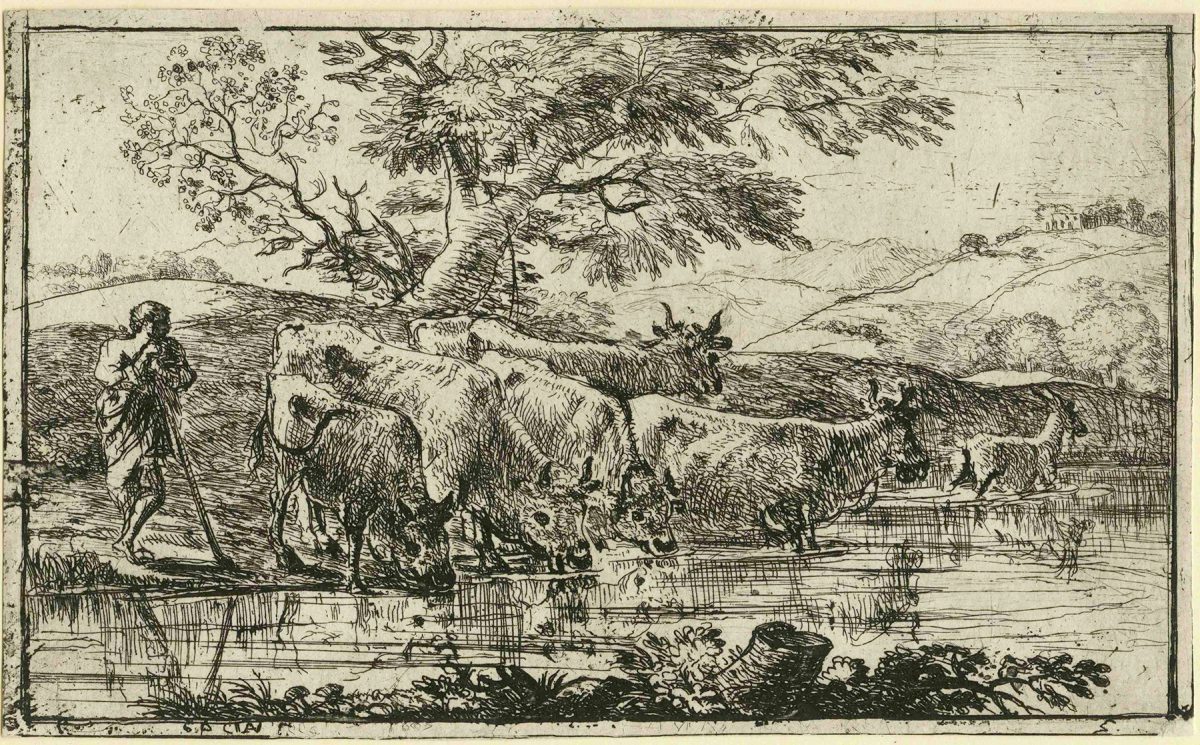

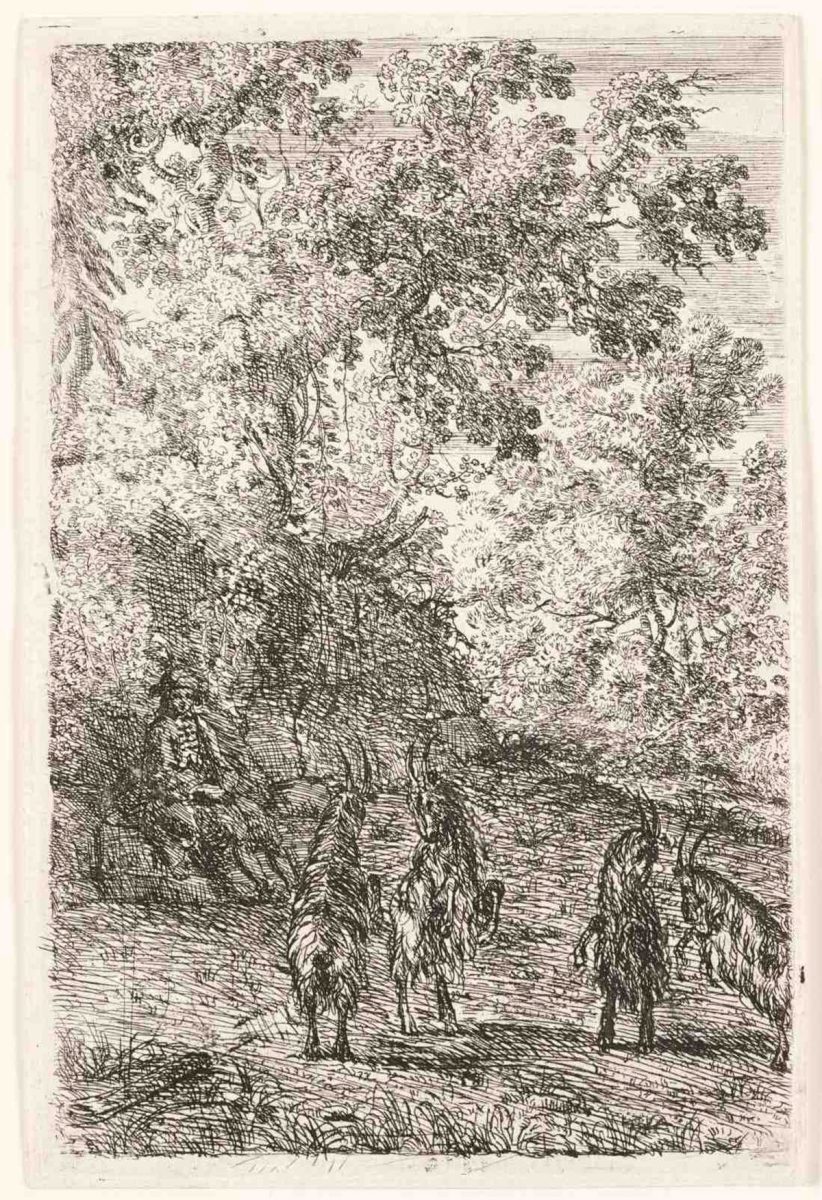

Though overshadowed by his paintings, Claude’s prints are nonetheless a rich body of work that sheds light on the artist's creative process. For Claude, engraving was neither a means of disseminating finished paintings nor a commercial venture, but rather an opportunity for free creative expression. Indeed, he often made several states of a single engraving, tweaking his plate to achieve just the right print. After his first experiments in etching the early 1630s, he made rapid progress with the medium. His prints from the later 1630s, which were sometimes based on pre-existing works, depict a more abundant and less ordered natural world than that which appears in his paintings. Between 1641 and the early 1650s, Claude gave up printmaking altogether, but he returned to it in his later years, producing masterpieces such as Le Troupeau en marche par temps orageux (The Herd Returning in Stormy Weather) in 1651, and Le Temps, Apollon et les Saisons (Time, Apollo and the Seasons) in 1662.